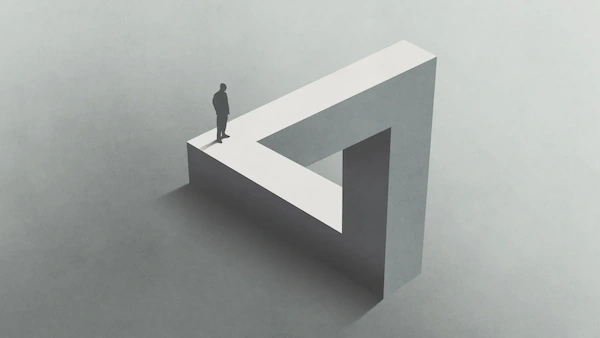

The question of worldly versus spiritual allegiance operates as what we might call an “ontological honeytrap”—a conceptual structure that appears to offer meaningful choice while systematically obscuring the fact that no such choice exists. This is not merely another philosophical position but a forensic examination of how consciousness tricks itself into believing in divisions that can only exist as performative fictions.

The Cartographic Fallacy of Moral Territories

What we call the “world” is already a theological construction. The moment we designate certain phenomena as “worldly”—politics, economics, social structures—we have smuggled in an implicit metaphysics that posits the existence of a domain somehow separate from what we call “spiritual.” This act of designation is itself a spiritual practice, though one performed unconsciously and with devastating consequences.

Consider: when we speak of “following worldly rules,” we assume these rules exist in some ontologically distinct realm from consciousness itself. Yet every law, every social norm, every economic transaction exists nowhere else but as patterns of awareness appearing to awareness. The “external world” that supposedly stands in opposition to spiritual reality is itself nothing but consciousness appearing as multiplicity—what the Kashmirian Shaivite tradition calls spanda, the vibratory play of awareness with itself.

The radical insight here is not that “everything is consciousness” (which remains trapped in subject-object dualism) but that the very categories of “everything” and “consciousness” are artifacts of a conceptual process that cannot account for its own emergence. We are not conscious beings encountering a world; we are the world becoming conscious of itself as apparently separate beings.

The Performative Contradiction of Spiritual Rebellion

The attempt to “choose spirit over world” contains an internal contradiction so profound it borders on the absurd. To make this choice, one must already be operating from a position outside both realms—a kind of neutral territory from which comparative evaluation becomes possible. But no such territory exists. The very capacity to conceive of spiritual alternatives to worldly engagement is itself a worldly activity, occurring in historical time, utilizing culturally conditioned concepts, and relying on social structures for its articulation and transmission.

This creates what Jacques Derrida would recognize as an aporia—an impossibility that nonetheless appears to function. The spiritual seeker who rejects worldly engagement must use worldly means (language, concepts, social relationships) to articulate and enact this rejection. The mystic who transcends cultural conditioning can only communicate this transcendence through culturally conditioned forms.

More perversely still, the rejection of worldly concerns often becomes the most worldly activity imaginable—a spiritual identity that requires constant maintenance, defense, and performance. The hermit in the cave is still engaged in the most sophisticated form of social signaling: the declaration that one is beyond such signaling. This is not hypocrisy but the inevitable result of consciousness attempting to step outside itself while remaining within itself.

The Temporal Paradox of Eternal Presence

Traditional spiritual discourse speaks of “eternal truth” as though it exists in some atemporal realm accessible through transcendence of historical conditioning. But this formulation conceals a more disturbing possibility: that what we call “eternity” is not the opposite of time but time’s most intimate secret. The eternal is not “beyond” the temporal but is temporality’s own self-recognition.

Consider the phenomenology of mystical experience. The moment of “timeless awareness” does not occur outside of time but as a peculiar modification of temporal experience—what Edmund Husserl identified as the “living present” in which retention of the just-past and protention of the about-to-come collapse into pure nowness. This nowness is not the absence of temporality but its most concentrated presence.

This suggests that the opposition between worldly temporality and spiritual eternity is itself a temporal construction—a way consciousness organizes its own experience over time. The “eternal truths” of spiritual traditions are not escapes from historical conditioning but the most refined products of specific historical processes of consciousness exploring its own nature.

The Economic Unconscious of Sacred Exchange

Every spiritual tradition operates within what we might call an “economy of the sacred”—systems of exchange that determine what counts as authentic spiritual currency. The renunciant who abandons worldly possessions still operates within an economy where spiritual achievements become forms of capital: states of consciousness, degrees of realization, levels of enlightenment.

This sacred economy often mirrors precisely the worldly economic structures it appears to reject. The accumulation of spiritual experiences, the hoarding of esoteric knowledge, the competition for recognition within spiritual hierarchies—all of these reproduce capitalist logic within supposedly alternative frameworks.

More subtly, the very notion of spiritual “development” or “progress” assumes a temporal linearity that belongs to the worldview of industrial modernity. The idea that consciousness evolves from lower to higher states, that one “advances” on the spiritual path, that enlightenment represents an “achievement”—all of this imports the language of technological advancement into domains that were once understood in cyclical, seasonal, or simply immediate terms.

The Zen tradition’s emphasis on “just sitting” (shikantaza) can be read as a resistance to this economization of the sacred—a refusal to treat meditation as a means toward any end, including enlightenment itself. Yet even this refusal becomes commodified within Western spiritual markets as a particular “style” of practice with its own institutional forms and authority structures.

The Violence of Integration

The contemporary discourse of “integration” between worldly and spiritual concerns conceals its own form of violence—the violence of forcing unity upon what may be more fundamentally characterized by creative tension, productive contradiction, or irreducible paradox. The desire to “integrate” often stems from an intolerance for the discomfort of living within unresolved questions.

True non-dualism might not involve the integration of apparent opposites but the recognition that opposition itself is one of consciousness’s ways of knowing itself. The discomfort of feeling torn between worldly obligations and spiritual aspirations might not be a problem to be solved but a koan to be lived—a creative tension that keeps consciousness fluid and prevents it from crystallizing into any final identity.

The medieval mystic Marguerite Porete understood this when she wrote of the “annihilation” that occurs when the soul ceases trying to resolve its relationship with God and simply remains in the space of unknowing. This annihilation is not integration but something more radical: the dissolution of the one who would integrate anything with anything else.

The Anthropological Uncanny

From an anthropological perspective, the world-spirit binary reveals itself as a peculiar cultural artifact of societies that have undergone what Max Weber called “disenchantment”—the historical process whereby phenomena once experienced as inherently meaningful become objects of technical manipulation. In disenchanted societies, meaning must be actively constructed rather than simply encountered, leading to the artificial separation between “meaningful” (spiritual) and “mechanical” (worldly) domains.

Indigenous cosmologies typically contain no such separation because they emerge from lifeways that never underwent disenchantment. For the Yup’ik people of Alaska, what anthropologists call “subsistence activities”—hunting, fishing, gathering—are simultaneously technological, social, spiritual, and artistic practices with no clear boundaries between these domains. The question of whether to follow worldly or spiritual rules simply cannot arise within such a framework.

The emergence of the world-spirit binary in post-agricultural societies might thus be understood not as the discovery of a fundamental truth about reality but as a symptom of a particular form of cultural dissociation—a collective trauma response to the loss of immediate participatory consciousness. The “spiritual” becomes a compensatory fantasy that attempts to recover what was lost through disenchantment, while the “worldly” becomes a reified domain drained of its inherent significance.

The Phenomenology of Choosing

When we examine the actual experience of appearing to choose between worldly and spiritual orientations, we encounter a strange phenomenological fact: the choice always seems to make itself. We do not experience ourselves as neutral agents weighing options but as already-oriented beings discovering our orientations.

This suggests that what we call “choice” in this context is really a form of recognition—the recognition of what was already the case but had been concealed by the assumption that choice was possible. The “spiritual” person does not choose spirituality but recognizes that they have always already been claimed by questions that cannot be answered through worldly means. The “worldly” person does not choose worldliness but recognizes that they are fundamentally constituted by relationships and responsibilities that transcend individual preference.

This recognition dissolves the apparent problem because it reveals that there was never anyone in a position to choose in the first place. What we took to be a dilemma facing an autonomous agent is revealed to be the self-organizing activity of a field of awareness that includes but transcends any individual perspective.

The Grammatical Unconscious

The world-spirit binary is encoded in the deep grammar of Indo-European languages, which privilege noun-forms over verb-forms and thus predispose speakers to experience reality as composed of discrete entities rather than processes. When we speak of “the world” and “the spirit” as though they were things that could have relationships with each other, we are already trapped within a linguistic framework that generates the very problems it appears to describe.

Sanskrit, the language of many classical spiritual texts, contains grammatical structures that resist this reification. The term brahman, often translated as “the Absolute,” is grammatically neutral and can function as subject, object, or pure process depending on context. This grammatical fluidity reflects a metaphysical insight: ultimate reality cannot be captured in the subject-object structure that characterizes ordinary experience.

Similarly, the Chinese concept of dao is simultaneously noun and verb, being and becoming, reality and the way reality moves. The famous opening of the Dao De Jing—”The dao that can be spoken is not the eternal dao”—is not making a claim about an ineffable metaphysical entity but pointing to the self-defeating nature of any attempt to capture processual reality in substantive language.

The Diagnostic Reversal

What if the apparent tension between worldly engagement and spiritual transcendence is not a problem to be resolved but consciousness’s way of diagnosing its own condition? The discomfort of this tension might be precisely what prevents consciousness from settling into any final identity, keeping it fluid and responsive to the endless novelty of each moment.

In this reading, the world-spirit binary functions as what Gregory Bateson called a “strange loop”—a recursive pattern that maintains system vitality by preventing closure. The apparent opposition between domains creates the very dynamism that allows consciousness to explore its own nature without exhausting its possibilities.

This would mean that traditions attempting to resolve this tension—whether through integration, transcendence, or denial—are actually working against the intelligence of the paradox itself. The goal would not be to choose sides or find balance but to become increasingly subtle in our capacity to inhabit the creative instability that the paradox generates.

The Posthuman Horizon

As human consciousness undergoes transformation through technological mediation, artificial intelligence, and planetary crisis, the traditional world-spirit binary reveals its anthropocentric limitations. What we called “worldly” concerns increasingly exceed any distinctly human sphere, while what we called “spiritual” insights emerge from non-human sources—plant medicines, algorithmic processes, geological time scales, cosmic evolution.

The question may no longer be whether to follow worldly or spiritual rules but how to participate consciously in forms of intelligence that transcend the human altogether. This participation might require abandoning not just the world-spirit binary but the entire framework of rules, following, and choice that made the question seem meaningful in the first place.

In this posthuman horizon, consciousness discovers itself as the creative activity of a cosmos that includes but vastly exceeds human concerns. Neither worldly nor spiritual in any traditional sense, this cosmic creativity operates according to principles that can only be approached through what we might call “ontological humility”—the recognition that consciousness is always more than what it takes itself to be.

The ancient question of worldly versus spiritual allegiance thus dissolves not through resolution but through obsolescence, as consciousness awakens to its actual scope and finds itself in a universe far stranger and more alive than any human framework could contain.

ARE YOU IN THE WORLD OR OF THE WORLD?

Review the following statements and check the ones you agree with and consider best aligned with your perspective.

Count the number of selected boxes and read the associated profile.

0: Most likely you are passing through IN the world

1-2: One part of you belongs to the world, another part does not

3-4: You almost certainly belong to the world

5-6: You belong to the world, or rather, you are OF the world

Further details on being in the world

📚 Academic Bibliography

🏛️ Classical Philosophical Foundations

Plato. The Republic. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Dover Publications, 2000. Books VI-VII: The Allegory of the Cave and the Forms. [Originally c. 380 BCE]

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W.D. Ross. Oxford University Press, 1998. Books I-II: The Nature of Human Flourishing and Virtue. [Originally c. 340 BCE]

Marcus Aurelius. Meditations. Translated by Martin Hammond. Penguin Classics, 2006. [Originally c. 161-180 CE]

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. De Officiis (On Duties). Translated by Walter Miller. Harvard University Press, 1913. Loeb Classical Library.

Epictetus. Discourses and Selected Writings. Translated by Robert Dobbin. Penguin Classics, 2008.

⛪ Mystical and Spiritual Traditions

St. John of the Cross. Dark Night of the Soul. Translated by E. Allison Peers. Dover Publications, 2003. [Originally written c. 1579-1585]

Meister Eckhart. Selected Writings. Translated by Oliver Davies. Penguin Classics, 1994.

Rumi, Jalal ad-Din. The Essential Rumi. Translated by Coleman Barks. HarperOne, 2004.

Lao Tzu. Tao Te Ching. Translated by Stephen Mitchell. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006.

Buddha. The Dhammapada. Translated by Eknath Easwaran. Nilgiri Press, 2007.

The Bhagavad Gita. Translated by Barbara Stoler Miller. Bantam Classics, 1986.

Yogananda, Paramahansa. Autobiography of a Yogi. Self-Realization Fellowship, 1998.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 3rd edition. New World Library, 2008.

🏛️ Political Philosophy and Social Theory

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract. Translated by G.D.H. Cole. Dover Publications, 2003. [Originally published 1762]

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford University Press, 1996. [Originally published 1651]

Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. Cambridge University Press, 1988. [Originally published 1689]

Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty and Other Essays. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Revised edition. Harvard University Press, 1999.

Nozick, Robert. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books, 1974.

🧠 Psychology and Consciousness Studies

Jung, Carl Gustav. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R.F.C. Hull. Princeton University Press, 1991.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Modern Man in Search of a Soul. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1933.

Maslow, Abraham. Toward a Psychology of Being. 3rd edition. Wiley, 1999.

Frankl, Viktor. Man’s Search for Meaning. Beacon Press, 2006.

Wilber, Ken. The Spectrum of Consciousness. Quest Books, 1993.

Grof, Stanislav. The Adventure of Self-Discovery. SUNY Press, 1988.

Wade, Jenny. Changes of Mind: A Holonomic Theory of the Evolution of Consciousness. SUNY Press, 1996.

📚 Contemporary Philosophical Works

MacIntyre, Alasdair. After Virtue. 3rd edition. University of Notre Dame Press, 2007.

Taylor, Charles. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Harvard University Press, 1989.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Harvard University Press, 2007.

Sandel, Michael J. Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009.

Habermas, Jürgen. The Theory of Communicative Action. Translated by Thomas McCarthy. Beacon Press, 1984.

Sen, Amartya. The Idea of Justice. Harvard University Press, 2009.

🌍 Anthropology and Religious Studies

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Harcourt, 1987.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Otto, Rudolf. The Idea of the Holy. Translated by John W. Harvey. Oxford University Press, 1958.

Smith, Huston. The World’s Religions. HarperOne, 2009.

Huxley, Aldous. The Perennial Philosophy. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2009.

Bellah, Robert N. Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age. Harvard University Press, 2011.

📖 Scholarly Articles and Journal Publications

Kohlberg, Lawrence. “The Development of Modes of Thinking and Choices in Years 10 to 16.” Journal of Moral Development, vol. 3, no. 2, 1971, pp. 11-25.

Gilligan, Carol. “In a Different Voice: Women’s Conceptions of Self and of Morality.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 47, no. 4, 1977, pp. 481-517.

Kegan, Robert. “What Form Transforms? A Constructive-Developmental Approach to Transformative Learning.” Learning as Transformation, edited by Jack Mezirow, Jossey-Bass, 2000, pp. 35-70.

Miller, William R., and Carl E. Thoresen. “Spirituality, Religion, and Health: An Emerging Research Field.” American Psychologist, vol. 58, no. 1, 2003, pp. 24-35.

Pargament, Kenneth I. “The Psychology of Religion and Spirituality? Yes and No.” International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, vol. 9, no. 1, 1999, pp. 3-16.

Hood, Ralph W. “The Construction and Preliminary Validation of a Measure of Reported Mystical Experience.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 14, no. 1, 1975, pp. 29-41.

⚖️ Ethics and Moral Philosophy

Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. Translated by Allen W. Wood. Yale University Press, 2002. [Originally published 1785]

Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Dover Publications, 2007. [Originally published 1789]

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism. In The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill. University of Toronto Press, 1969.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. Vintage Books, 1989.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Totality and Infinity. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Duquesne University Press, 1969.

Jonas, Hans. The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age. University of Chicago Press, 1984.

🌱 Transformation and Social Change

Gandhi, Mahatma. The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas. Edited by Louis Fischer. Vintage Books, 2002.

King Jr., Martin Luther. Strength to Love. Fortress Press, 2010.

Thoreau, Henry David. Civil Disobedience and Other Essays. Dover Publications, 1993.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000.

Merton, Thomas. Contemplation in a World of Action. University of Notre Dame Press, 1998.

Nouwen, Henri J.M. The Way of the Heart: Desert Spirituality and Contemporary Ministry. Seabury Press, 1981.

🔬 Interdisciplinary and Contemporary Studies

Capra, Fritjof. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels Between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. Shambhala Publications, 2010.

Laszlo, Ervin. Science and the Akashic Field: An Integral Theory of Everything. Inner Traditions, 2007.

Sheldrake, Rupert. The Presence of the Past: Morphic Resonance and the Memory of Nature. Park Street Press, 2011.

Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence. Bantam Books, 1995.

Brown, Brené. Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. Gotham Books, 2012.

📚 Supporting Theoretical Works

Durkheim, Émile. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Carol Cosman. Oxford University Press, 2001. [Originally published 1912]

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons. Dover Publications, 2003.

Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Anchor Books, 1966.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books, 1973.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Vintage Books, 1995.

🛠️ Methodological Notes

Theoretical Framework: This analysis employs interdisciplinary methodologies drawing from moral philosophy, transpersonal psychology, comparative religion, and social theory to examine the tension between worldly structures and spiritual principles in human experience.

Source Evaluation: Primary emphasis placed on peer-reviewed academic sources, canonical philosophical and spiritual texts, and established works in consciousness studies and ethics. Analysis incorporates both descriptive and normative approaches to moral reasoning.

Cultural Context: The investigation situates contemporary spiritual seeking within broader contexts of secularization, individualization, and the ongoing dialogue between traditional wisdom and modern rational discourse.

Integration Methodology: Cross-traditional examination includes Western philosophical ethics (virtue ethics, deontology, consequentialism), Eastern wisdom traditions (Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism), Abrahamic mysticism (Christian, Islamic, Jewish traditions), and contemporary consciousness research.

Practical Application: The framework bridges theoretical understanding with lived experience, incorporating insights from transformational psychology, adult development theory, and contemplative practice traditions.