The Great Forgetting: From Wisdom to Mere Knowledge

The Platonic Cave Revisited: Modern Shadows on Ancient Walls

Twenty-five centuries ago, Heraclitus proclaimed that “the path up and down are one and the same”—a cryptic utterance that reveals the cyclical nature of human civilization. We have completed a full revolution from ancient wisdom back to primitive materialism, yet we mistake our descent for progress. What the ancients understood through contemplation, we have forgotten through accumulation.

Plato’s allegory of the cave has never been more relevant. Modern humanity sits chained before shadows on a wall, mistaking these flickering images—our possessions, achievements, and digital personas—for reality itself. The philosopher-king who escapes to contemplate the Forms and returns to share this wisdom is now dismissed as impractical, while the shadow-watchers celebrate their expertise in predicting which shadow will appear next.

The Aristotelian Trinity: Knowledge Without Wisdom

Aristotle distinguished between three types of knowledge: episteme (theoretical knowledge), techne (practical skill), and phronesis (practical wisdom). Our age has mastered the first two while abandoning the third—the very capacity that Aristotle considered essential for human flourishing (eudaimonia). We possess unprecedented technical power but lack the wisdom to wield it well, like children playing with fire who marvel at its brightness while ignoring its capacity to burn.

The Stoic Paradox: Having Less to Gain More

The Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius observed in his Meditations that “very little is needed to make a happy life.” Yet contemporary society operates on the inverse principle—that happiness requires accumulating ever more experiences, possessions, and achievements. We have forgotten what Epictetus taught: that freedom comes not from having more, but from wanting less; not from controlling circumstances, but from mastering our responses to them.

The Socratic Ignorance: Knowing That We Do Not Know

The Oracle’s Wisdom: Sacred Ignorance as Philosophical Foundation

Socrates earned the title of wisest man in Athens because he alone knew that he knew nothing. This docta ignorantia—learned ignorance—represents the beginning of true philosophy. Modern education, however, operates on the opposite principle: we stuff students with information while never teaching them the profound humility that opens the mind to wisdom.

The Socratic method reveals truth through questioning rather than instruction, through aporia (puzzlement) rather than certainty. Yet our educational systems reward quick answers over deep questions, memorization over contemplation, and information accumulation over the cultivation of wonder—what Aristotle called the beginning of philosophy.

Socrates understood that the unexamined life is not worth living because examination reveals the fundamental questions that give life meaning: What is justice? What is courage? What is the good life? How should we die? These questions cannot be answered through Google searches or technical manuals; they require the patient work of dialectical inquiry and contemplative reflection.

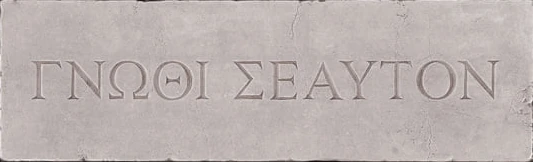

The Delphic Command: Know Thyself in an Age of External Obsession

The Oracle at Delphi’s command to “know thyself” (gnothi seauton) has become perhaps the most ignored wisdom in human history. We know more about distant galaxies than about our own souls, more about artificial intelligence than about natural wisdom, more about optimizing external performance than about cultivating inner peace.

The Platonic Ascent: From Shadows to Light

The Inverted Hierarchy: When Shadows Rule the Cave

Plato’s divided line illustrates the hierarchy of knowledge: from eikasia (imagination/illusion) through pistis (belief) and dianoia (thought) to noesis (direct intellectual apprehension). Modern culture has inverted this hierarchy, privileging sensory experience and mathematical calculation while dismissing the higher forms of knowing that apprehend eternal truths.

In the Republic, Plato demonstrates that justice in the soul parallels justice in the state: when reason rules over appetite through the mediation of spirit, harmony results. Our contemporary crisis stems from appetite ruling over reason—desire determining thought rather than wisdom guiding action. The cave-dwellers have overthrown the philosopher-kings and declared their shadows to be the highest reality.

The theory of Forms reveals that material objects participate in eternal patterns that exist beyond space and time. A just action reflects the Form of Justice; a beautiful sunset participates in the Form of Beauty; a courageous deed embodies the Form of Courage. When we focus solely on material particulars while ignoring their eternal archetypes, we lose access to the very standards that make evaluation possible.

The Damaged Wings: How Materialism Grounds the Soul

Plato’s Phaedrus describes the soul’s wings being damaged by materialistic pursuits, causing it to fall from contemplation of eternal truths into obsession with temporal concerns. The winged soul naturally soars toward wisdom, beauty, and goodness, but material attachments weigh it down like lead. Contemporary culture systematically damages these wings through constant distraction and stimulation.

The Aristotelian Synthesis: Excellence as Habit

The Golden Mean: Virtue Between Extremes

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics defines virtue (arete) as excellence of character developed through habituation (hexis). We become courageous by acting courageously, temperate by practicing temperance, generous by giving generously. Character is not formed through inspiration or information, but through the patient repetition of excellent actions until they become second nature.

The doctrine of the golden mean reveals that excellence lies between extremes of excess and deficiency. Courage stands between cowardice and recklessness; generosity between stinginess and wastfulness; pride between vanity and servility. Yet modern culture promotes extremes: extreme ambition, extreme pleasure-seeking, extreme individualism, extreme materialism—all of which lead away from the harmonious center where virtue resides.

The Three Friendships: Utility, Pleasure, and Virtue

Aristotle’s analysis of friendship distinguishes between relationships based on utility, pleasure, and virtue. Only friendships grounded in mutual appreciation of each other’s character (philia) provide lasting satisfaction. Contemporary relationships often focus on what people can do for us (utility) or how they make us feel (pleasure) rather than who they are in their essential being (virtue).

Eudaimonia: The Misunderstood Good Life

The concept of eudaimonia—often translated as happiness but meaning something closer to “flourishing” or “living well”—cannot be achieved through external circumstances alone. Aristotle argues that eudaimonia requires virtuous activity in accordance with our highest capacities over a complete lifetime. It is an activity (energeia) of the soul, not a feeling or possession.

The Stoic Cosmos: Living in Harmony with Nature

The Cosmic Symphony: Humanity’s Place in the Divine Order

The Stoics understood that humans are rational fragments of the divine Logos—the rational principle that governs the cosmos. Marcus Aurelius writes, “Constantly regard the universe as one living being, having one substance and one soul.” This cosmic perspective dissolves petty anxieties and reveals our place within the grand symphony of existence.

The Great Dichotomy: What Is and Isn’t Up to Us

Epictetus taught the fundamental distinction between what is “up to us” (eph’ hemin) and what is “not up to us” (ouk eph’ hemin). Our judgments, desires, and actions are within our control; everything else—reputation, wealth, health, even life itself—lies beyond our direct influence. Freedom comes from focusing energy exclusively on what lies within our power while accepting what lies beyond it.

Sympatheia: The Sacred Web of Cosmic Connection

The Stoic concept of sympatheia reveals the interconnectedness of all things within the cosmic web. As Marcus Aurelius observes, “All things are woven together and the common bond is sacred.” This understanding transforms individual suffering into participation in cosmic necessity and individual action into contribution to universal harmony.

Seneca’s Letters: Philosophy as Daily Practice

Seneca’s letters to Lucilius demonstrate practical philosophy in action: how to face death without fear, how to enjoy pleasures without attachment, how to endure suffering with dignity, how to act virtuously regardless of consequences. These are not abstract theories but lived wisdom forged in the crucible of experience.

The Eastern Mirror: Complementary Truths

The Tao That Cannot Be Spoken: Beyond Conceptual Grasping

Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching begins with the profound recognition that “the Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao.” This apophatic approach—knowing through unknowing—parallels Socratic ignorance and Platonic mysticism. The highest truths cannot be grasped through conceptual thinking but must be lived through harmonious action.

Wu Wei: The Art of Non-Forcing Action

The Taoist principle of wu wei—non-forcing action—teaches that the most effective activity flows from alignment with natural patterns rather than aggressive assertion of will. Like water, which overcomes rock through persistence rather than force, wisdom achieves its aims through patient yielding rather than violent striving.

The Buddhist Diagnosis: Suffering as Existential Teacher

The Buddhist recognition of dukkha (suffering), anicca (impermanence), and anatta (non-self) provides a diagnostic analysis of human dissatisfaction. We suffer because we grasp after permanent satisfaction in an impermanent world, seeking solid identity in a process of constant change. Liberation comes through releasing these impossible demands rather than fulfilling them.

Maya and Brahman: The One Playing at Being Many

The Hindu understanding of maya (illusion) suggests that our ordinary perception of reality as composed of separate, independent objects is fundamentally mistaken. What appears as multiplicity is actually the play of one underlying consciousness (Brahman) manifesting itself in countless forms. This insight transforms competition into cooperation and isolation into communion.

The Christian Synthesis: Love as Ultimate Reality

Augustine’s Restless Heart: The Soul’s Eternal Homesickness

Augustine’s Confessions reveals the restless heart that finds peace only in God: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” This existential analysis locates the source of modern anxiety in misdirected love—amor sui (love of self) rather than amor Dei (love of God).

Aquinas and the Marriage of Reason and Faith

Thomas Aquinas’s synthesis of Aristotelian philosophy and Christian revelation demonstrates that reason and faith point toward the same truth when properly understood. The natural desire for happiness finds its ultimate fulfillment in the beatific vision—direct contemplation of divine goodness that satisfies every longing while generating no new desires.

Meister Eckhart’s Gelassenheit: Divine Letting-Go

The mystic Meister Eckhart taught that the highest human activity is “letting go and letting be”—creating space within the soul for divine activity to manifest. This Gelassenheit (releasement) transcends both grasping and rejecting to achieve perfect receptivity to grace.

The Dark Night: Collective Spiritual Crisis as Purification

Saint John of the Cross described the “dark night of the soul” as the necessary purification that precedes mystical union. The apparent absence of meaning and purpose that characterizes modern life may represent this dark night on a collective scale—a spiritual crisis that precedes breakthrough to higher consciousness.

The Renaissance Recovery: Humanity Between Beasts and Angels

Pico’s Oration: The Dignity of Radical Freedom

Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man portrays humans as uniquely positioned between the material and spiritual realms, capable of descending to brutish materialism or ascending to angelic contemplation. This freedom represents both our greatest gift and our most dangerous responsibility.

Ficino’s Platonic Revival: Rediscovering Divine Madness

Marsilio Ficino’s translation and interpretation of Plato initiated a revival of contemplative philosophy that influenced art, literature, and spirituality for centuries. His understanding of furor divinus (divine madness) revealed how poetic inspiration, prophetic vision, and mystical experience represent higher forms of rationality rather than departures from it.

The Foundation of Human Dignity

The Renaissance concept of dignitas hominis (human dignity) grounds ethical obligation in metaphysical reality: humans possess intrinsic worth because they participate in divine nature through reason and free will. This dignity cannot be earned or lost but can be honored or violated through our choices.

The Modern Forgetting: From Being to Having

The Cartesian Split: Mind Divorced from World

The transition from medieval to modern consciousness represents what we might call “the great flattening”—the reduction of reality’s vertical dimension (the hierarchy of being from matter through soul to spirit) to pure horizontality (material interactions governed by mechanical laws).

René Descartes’ separation of mind and matter, while solving certain technical problems, created the metaphysical crisis that still haunts Western civilization: if consciousness is separate from nature, how can we find meaning in a purely material world? The Cartesian split makes nature into dead matter and consciousness into isolated subjectivity.

Bacon’s Conquest: Knowledge as Power Over Nature

Francis Bacon’s program for the “conquest of nature” through experimental science transforms the ancient ideal of contemplative union with reality into aggressive domination over it. Knowledge becomes power rather than wisdom, and nature becomes resource rather than teacher.

🎁 Spiritual Gifts & Talents Test

Unveil your soul’s sacred purpose by identifying your unique spiritual endowments. These gifts—whether wisdom that illuminates darkness, creativity that brings beauty from chaos, empathy that heals wounded hearts, or leadership that transforms communities—are sacred threads woven into the fabric of your soul.

Drawing from humanity’s great wisdom traditions, this assessment explores 17 distinct spiritual gifts, each representing a different facet of divine expression through human experience.

❓25 questions

💬 5 possible answers

👤 17 different gifts/talents

Hobbes’s War: Life Without Cosmic Purpose

Thomas Hobbes’s description of life as “nasty, brutish, and short” without strong government reflects the loss of cosmic vision that once located individual existence within meaningful larger wholes. When humans are seen as isolated material beings competing for scarce resources, society becomes a war of all against all.

The Necessity of Uncertainty: Aporia as Gateway to Wisdom

Socratic Puzzlement: The Fertile Ground of Wonder

The Socratic understanding of uncertainty (aporia) reveals what modern culture desperately tries to avoid: that the most profound questions admit no easy answers. Socrates deliberately cultivated puzzlement in his interlocutors not to frustrate them, but to awaken them from the dogmatic slumber of false certainty. “I know that I know nothing,” he proclaimed—not as defeat, but as the beginning of true inquiry.

Aristotle observed that wonder (thaumazein) is the origin of philosophy. We begin to think seriously only when our comfortable assumptions are shattered, when the familiar becomes strange, when questions emerge that cannot be answered through conventional wisdom. The person who experiences no fundamental uncertainty has never begun to philosophize.

Stoic Tranquility: Embracing Life’s Groundlessness

The Stoics taught that uncertainty about external circumstances is the natural human condition. We cannot know whether we will live or die tomorrow, whether our plans will succeed or fail, whether our loved ones will remain healthy or fall ill. Epictetus counseled that tranquility comes not from eliminating uncertainty but from accepting it as the very structure of mortal existence. “Don’t demand that things happen as you wish,” he taught, “but wish that they happen as they do happen.”

Buddhist Impermanence: The Liberation of Letting Go

Buddhism identifies uncertainty (anicca – impermanence) as one of the three fundamental characteristics of existence. The attempt to find permanent security in an impermanent world is the root of all suffering (dukkha). Liberation comes through embracing rather than fleeing from life’s essential groundlessness.

The Sacred Nature of Dissatisfaction: Divine Discontent

Augustine’s Inquietum Cor: The Heart’s Eternal Unrest

Augustine’s profound insight that “our hearts are restless until they rest in God” reveals dissatisfaction not as a problem to be solved but as the very mechanism through which the soul seeks its true home. This divine discontent (inquietum cor) prevents us from settling for partial goods and drives us toward the infinite.

Platonic Eros: Love as Philosophical Ascent

Plato’s Symposium describes eros (love) as fundamentally lacking—we love only what we do not possess. This lack is not a deficiency but the engine of philosophical ascent. The lover of wisdom (philosophos) occupies the middle ground between ignorance and complete knowledge, forever seeking what remains just beyond reach.

Rumi’s Wound: Where Light Enters the Soul

The Persian Sufi poet Rumi understood that the pain of separation from the Beloved is actually the Beloved’s presence in disguised form: “The wound is the place where the Light enters you.” Similarly, existential dissatisfaction may be the soul’s recognition that it belongs to a realm higher than material existence.

The Aristotelian Analysis: Why Pleasure Cannot Satisfy

Aristotle’s analysis reveals that happiness (eudaimonia) cannot consist in pleasure alone because pleasure is momentary while happiness must endure over a complete lifetime. The hedonic treadmill that characterizes modern life—constantly seeking the next acquisition, achievement, or experience—reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of human nature. We are dissatisfied by temporary pleasures precisely because we are designed for something higher.

Medieval Acedia: The Sin of Spiritual Sloth

The medieval concept of acedia—spiritual dryness or sloth—was considered one of the deadliest sins not because it involved active wickedness but because it represented despair about the possibility of spiritual progress. Contemporary culture’s epidemic of depression and anxiety may reflect this same spiritual condition: the soul’s recognition that material pursuits cannot satisfy its deepest longings.

The Severing of Wisdom Traditions: When Elders Lose Their Voice

Plato’s Laws: The Transmission of Accumulated Wisdom

In Plato’s Laws, the elderly statesman from Athens explains that societies flourish when accumulated wisdom passes from generation to generation through living example and careful instruction. The breakdown of this transmission creates what we might call “cultural amnesia”—each generation forced to rediscover basic truths about human nature and the good life.

Aristotelian Phronesis: Wisdom Through Lived Experience

Aristotle emphasized that practical wisdom (phronesis) develops only through long experience of making difficult choices and living with their consequences. The young possess energy and intelligence but lack the seasoned judgment that comes from observing the full arc of human actions and their results. When societies fail to honor this wisdom or create structures for its transmission, they condemn each new generation to repeat ancient errors.

Confucian Life Stages: The Path to Mature Understanding

The ancient Chinese concept of filial piety (xiao) recognized that honoring elders serves not merely social cohesion but the preservation and development of wisdom itself. Confucius taught that learning from those who have lived long and reflected deeply is essential for moral development: “At fifteen, I set my heart on learning; at thirty, I established myself; at forty, I had no more doubts; at fifty, I understood the mandate of Heaven; at sixty, my ear was attuned; at seventy, I could follow my heart’s desire without transgressing what was right.”

The Hindu Ashrama: Sacred Stages of Spiritual Development

The Hindu tradition of ashrama (life stages) designates the final phase of life as sannyasa—the period when worldly concerns are set aside for spiritual instruction and contemplation. The elderly sannyasi becomes a teacher precisely because he has experienced the full range of human possibilities and recognized their ultimate limitations. This wisdom cannot be learned from books or acquired through technique; it emerges only from the patient endurance of life’s complete curriculum.

The Metaphysical Catastrophe: Cultural Autism and Lost Eldership

The loss of eldership in contemporary society represents more than sociological change; it constitutes a metaphysical catastrophe. When societies privilege youth over age, innovation over tradition, and technical skill over wisdom, they cut themselves off from their own roots. The resulting “cultural autism” leaves each individual isolated in their own immediate experience, unable to benefit from humanity’s accumulated understanding of life’s fundamental patterns.

Marcus Aurelius on Mortality: The Wisdom of Transience

Marcus Aurelius, writing as an older man who had experienced both the heights of imperial power and the depths of personal loss, reflected: “Soon you will have forgotten everything, and soon everyone will have forgotten you.” Yet this apparent nihilism contains profound wisdom: only by accepting the transience of all earthly achievements can we focus on what truly matters—the cultivation of virtue and wisdom that transcends individual mortality.

Celtic Soul Friends: The Tradition of Spiritual Guidance

The Celtic tradition of the anamchara (soul friend) recognized that spiritual guidance requires not just knowledge but the lived experience of spiritual struggle and breakthrough. The elder who has wrestled with doubt, survived loss, faced mortality, and discovered meaning beyond material circumstances possesses irreplaceable gifts for those beginning their own journeys.

The Hubris of Youth Culture: Rejecting Ancestral Wisdom

Contemporary culture’s youth obsession reflects what the Greeks called hubris—the arrogant assumption that each generation can surpass all previous ones through cleverness and innovation alone. This hubris cuts young people off from what the Romans called majorum sapientia—the wisdom of their ancestors—leaving them vulnerable to precisely those errors that previous generations learned to avoid through painful experience.

The Eclipse of Moral Philosophy: When Ethics Becomes Opinion

Aristotelian Teleology: The Highest Good as Life’s Aim

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics begins with the profound observation that every action aims at some good, and that there exists a highest good (summum bonum) toward which all other goods are ordered. Contemporary culture has abandoned this teleological understanding, reducing ethics to personal preference or social convention rather than recognizing moral truth as objective reality discoverable through reason and experience.

Platonic Justice: Morality as Cosmic Order

Plato’s Republic demonstrates that justice is not merely useful social arrangement but corresponds to the very structure of reality itself. The just soul mirrors the cosmic order where reason rules over appetite through the mediation of spirit. When societies lose this metaphysical grounding for ethics, moral discourse degenerates into power struggles between competing interests rather than collaborative inquiry into truth.

Stoic Virtue: The Only True Good

The Stoics understood that virtue (arete) is the only true good because it alone remains within our complete control regardless of external circumstances. Epictetus taught that we can lose our possessions, reputation, health, and even life, but no one can force us to act unjustly without our consent. This insight transforms ethics from external compliance with rules into internal cultivation of character.

Thomistic Natural Law: Universal Moral Principles

Thomas Aquinas’s synthesis reveals that natural law (lex naturalis) provides universal ethical principles accessible to human reason across all cultures and times. The fundamental precepts—preserve life, educate children, live in society, worship God—reflect the rational structure of human nature itself. When education abandons these perennial principles for cultural relativism, it leaves students without moral compass in an ethically complex world.

Kant’s Categorical Imperative: The Test of Moral Universality

Kant’s categorical imperative—”Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”—provides a rational test for moral action that transcends personal desire or social pressure. Yet this formal principle requires substantial moral formation to apply wisely. Without cultivation of practical wisdom (phronesis) through habituation in virtue, even the best ethical theories remain empty abstractions.

The Contemporary Crisis: Techniques Without Purposes

The contemporary crisis stems not from lack of ethical theories but from the systematic elimination of moral formation from education and culture. Students learn techniques for achieving desired outcomes but receive no training in discerning which outcomes are worth desiring. They master means while remaining ignorant of proper ends.

Beyond Mere Survival: The Human Calling to Transcendence

The Aristotelian Soul: Rising Above Animal Existence

Aristotle’s doctrine of the soul distinguishes between nutritive, sensitive, and rational functions. Humans share nutrition with plants and sensation with animals, but reason (nous) constitutes our distinctive capacity. A life devoted solely to biological survival and material comfort exercises only our lowest capacities while neglecting what makes us specifically human.

Platonic Harmony: The Soul’s Three-Part Symphony

The Platonic understanding of the soul’s three parts—appetite (epithumia), spirit (thumos), and reason (logos)—reveals that authentic human fulfillment requires the harmonious development of all dimensions under reason’s guidance. A life governed purely by appetite reduces humans to the level of beasts; one governed by spirit alone creates warriors without wisdom; only reason can integrate all capacities toward genuine flourishing.

Marcus Aurelius and Cosmic Participation

Marcus Aurelius reflected that humans are distinguished from other animals by their capacity to contemplate the cosmic order and align their individual will with universal reason. “You came from nothing and will return to nothing,” he wrote, “so what have you lost?” This apparent nihilism actually points toward transcendence: by accepting the transience of material existence, we discover our participation in eternal patterns of truth, beauty, and goodness.

Stoic Sympatheia: Individual Meaning Through Universal Connection

The Stoic concept of sympatheia reveals that individual human existence gains meaning through conscious participation in the rational order of the cosmos. We are not isolated biological units competing for resources, but rational fragments of divine reason (logos) capable of understanding and cooperating with the whole. This cosmic perspective transforms survival from mere self-preservation into conscious contribution to universal harmony.

Augustine’s Two Cities: Temporal Goods and Eternal Purposes

Saint Augustine’s analysis of the two cities—the earthly city devoted to temporal goods and the heavenly city ordered toward eternal truth—shows that humans inevitably organize their lives around either finite or infinite goods. Those who make survival and material prosperity their highest aims condemn themselves to perpetual anxiety, since these goods are always threatened by loss. Only by ordering temporal goods toward eternal ones can we achieve the peace that comes from pursuing truly adequate objects of love.

Aquinas and the Intellectual Desire for God

Thomas Aquinas’s demonstration that the human intellect naturally desires to know the essence of God reveals that our rational nature inherently transcends any finite good. Even if we possessed unlimited wealth, health, pleasure, and power, the mind would still seek to understand the source and meaning of existence itself. This restless intellectual desire (desiderium naturale) proves that humans are called to beatific vision—direct contemplation of divine truth—as their ultimate end.

The Liberal Arts: Education for Freedom, Not Servitude

The medieval understanding of the seven liberal arts—grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music—aimed not at professional training but at liberating the mind from bondage to material necessity. These studies cultivate what the ancients called otium—leisure devoted to contemplation—as opposed to negotium—business devoted to survival and material gain. Only minds freed from exclusive focus on practical necessities can engage the highest questions about reality, meaning, and purpose.

Plotinian Epistrophe: The Soul’s Return to Unity

Plotinus taught that the soul’s natural movement is toward unity with the One—the source of all being, truth, and beauty. This epistrophe (return) requires progressively detaching attention from material multiplicity to discover the spiritual unity underlying apparent diversity. The soul that remains focused solely on survival and material accumulation moves away from rather than toward its true home.

Hindu Dharma: Sacred Duty Beyond Biological Imperatives

The Hindu concept of dharma reveals that each individual has a sacred duty (svadharma) that transcends biological survival. The Bhagavad Gita‘s teaching about acting without attachment to results (nishkama karma) shows how even ordinary activities become spiritual practices when performed as offerings to the divine rather than means of self-aggrandizement.

The Contemporary Wasteland: Nihilism as Spiritual Crisis

Nietzsche’s Diagnosis: God is Dead, Now What?

Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation that “God is dead” diagnoses rather than celebrates the loss of transcendent meaning that makes ethical action possible. His concept of the Übermensch represents an attempt to create new values after the old ones have collapsed, but this project requires precisely the kind of spiritual greatness that materialistic culture systematically undermines.

The Logic of Materialism: From Atoms to Meaninglessness

The phenomenon of nihilism—the belief that nothing has ultimate meaning—represents the logical endpoint of materialistic reductionism. If humans are merely complex arrangements of matter governed by physical laws, then our deepest experiences of love, beauty, truth, and goodness become evolutionary accidents with no cosmic significance.

The Dark Night of Culture: Crisis as Prelude to Awakening

Yet this spiritual crisis contains the seeds of renewal. As Nietzsche himself recognized, those who can endure the abyss of meaninglessness without succumbing to despair may discover new sources of value grounded in life itself rather than external authorities. The dark night of cultural meaninglessness may precede a new dawn of spiritual awakening.

The Perennial Solution: Philosophy as Spiritual Practice

Philosophy as Love of Wisdom: Beyond Academic Speculation

The ancient understanding of philosophy as love of wisdom (philosophia) rather than mere academic speculation offers the key to our contemporary crisis. Philosophy practiced as spiritual discipline transforms both knower and known, both seeker and truth sought.

The Convergent Path: Many Methods, One Transformation

The Platonic path of dialectical ascent, the Aristotelian cultivation of virtue through habituation, the Stoic alignment with cosmic reason, the Buddhist liberation from attachment, the Taoist harmony with natural flow, the Christian surrender to divine love—all these represent methods for the same fundamental transformation: the shift from ego-centered existence to reality-centered being.

Practice Over Theory: The Necessity of Lived Wisdom

This transformation cannot be achieved through reading books or attending lectures, though these may help. It requires the sustained practice of attention, the cultivation of virtue through action, the development of discernment through experience, and the patient endurance of uncertainty while truth gradually reveals itself.

The Eternal Return: Every Generation’s Spiritual Task

The contemporary crisis of meaning thus represents not a unique historical predicament but the perennial human situation made visible through the stripping away of cultural supports. Every generation must rediscover for itself the eternal truths that make life worth living. Our task is neither to create new values nor to restore old ones, but to awaken to the timeless wisdom that has always been available to those willing to undertake the philosopher’s journey from opinion to knowledge, from appearance to reality, from temporal concerns to eternal truths.

Conclusion: The Great Work of Our Time

The Ancient Imperatives: Know Thyself, Live Virtuously, Love Wisdom

The path remains what it has always been: know thyself, live virtuously, contemplate reality, love wisdom, serve truth. These ancient imperatives shine with renewed urgency in our age of distraction and confusion. They offer not escape from contemporary challenges but the spiritual foundation necessary for meeting them with wisdom, courage, and compassion.

The Search That Gives Meaning to Itself

In the end, philosophical and spiritual research represents humanity’s highest calling: the search for meaning that gives meaning to the search itself. This is the Great Work that each soul must undertake, the inner journey that makes all outer journeys worthwhile, the eternal quest that transforms both seeker and sought in the very seeking. Outcomes are worth desiring. They master means while remaining ignorant of proper ends.

Beyond Mere Survival: The Human Calling to Transcendence

Aristotle’s doctrine of the soul distinguishes between nutritive, sensitive, and rational functions. Humans share nutrition with plants and sensation with animals, but reason (nous) constitutes our distinctive capacity. A life devoted solely to biological survival and material comfort exercises only our lowest capacities while neglecting what makes us specifically human.

The Platonic understanding of the soul’s three parts—appetite (epithumia), spirit (thumos), and reason (logos)—reveals that authentic human fulfillment requires the harmonious development of all dimensions under reason’s guidance. A life governed purely by appetite reduces humans to the level of beasts; one governed by spirit alone creates warriors without wisdom; only reason can integrate all capacities toward genuine flourishing.

Marcus Aurelius reflected that humans are distinguished from other animals by their capacity to contemplate the cosmic order and align their individual will with universal reason. “You came from nothing and will return to nothing,” he wrote, “so what have you lost?” This apparent nihilism actually points toward transcendence: by accepting the transience of material existence, we discover our participation in eternal patterns of truth, beauty, and goodness.

The Stoic concept of sympatheia reveals that individual human existence gains meaning through conscious participation in the rational order of the cosmos. We are not isolated biological units competing for resources, but rational fragments of divine reason (logos) capable of understanding and cooperating with the whole. This cosmic perspective transforms survival from mere self-preservation into conscious contribution to universal harmony.

Saint Augustine’s analysis of the two cities—the earthly city devoted to temporal goods and the heavenly city ordered toward eternal truth—shows that humans inevitably organize their lives around either finite or infinite goods. Those who make survival and material prosperity their highest aims condemn themselves to perpetual anxiety, since these goods are always threatened by loss. Only by ordering temporal goods toward eternal ones can we achieve the peace that comes from pursuing truly adequate objects of love.

Thomas Aquinas’s demonstration that the human intellect naturally desires to know the essence of God reveals that our rational nature inherently transcends any finite good. Even if we possessed unlimited wealth, health, pleasure, and power, the mind would still seek to understand the source and meaning of existence itself. This restless intellectual desire (desiderium naturale) proves that humans are called to beatific vision—direct contemplation of divine truth—as their ultimate end.

The medieval understanding of the seven liberal arts—grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music—aimed not at professional training but at liberating the mind from bondage to material necessity. These studies cultivate what the ancients called otium—leisure devoted to contemplation—as opposed to negotium—business devoted to survival and material gain. Only minds freed from exclusive focus on practical necessities can engage the highest questions about reality, meaning, and purpose.

Plotinus taught that the soul’s natural movement is toward unity with the One—the source of all being, truth, and beauty. This epistrophe (return) requires progressively detaching attention from material multiplicity to discover the spiritual unity underlying apparent diversity. The soul that remains focused solely on survival and material accumulation moves away from rather than toward its true home.

The Hindu concept of dharma reveals that each individual has a sacred duty (svadharma) that transcends biological survival. The Bhagavad Gita‘s teaching about acting without attachment to results (nishkama karma) shows how even ordinary activities become spiritual practices when performed as offerings to the divine rather than means of self-aggrandizement.

The Contemporary Wasteland: Nihilism as Spiritual Crisis

Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation that “God is dead” diagnoses rather than celebrates the loss of transcendent meaning that makes ethical action possible. His concept of the Übermensch represents an attempt to create new values after the old ones have collapsed, but this project requires precisely the kind of spiritual greatness that materialistic culture systematically undermines.

The phenomenon of nihilism—the belief that nothing has ultimate meaning—represents the logical endpoint of materialistic reductionism. If humans are merely complex arrangements of matter governed by physical laws, then our deepest experiences of love, beauty, truth, and goodness become evolutionary accidents with no cosmic significance.

Yet this spiritual crisis contains the seeds of renewal. As Nietzsche himself recognized, those who can endure the abyss of meaninglessness without succumbing to despair may discover new sources of value grounded in life itself rather than external authorities. The dark night of cultural meaninglessness may precede a new dawn of spiritual awakening.

The Perennial Solution: Philosophy as Spiritual Practice

The ancient understanding of philosophy as love of wisdom (philosophia) rather than mere academic speculation offers the key to our contemporary crisis. Philosophy practiced as spiritual discipline transforms both knower and known, both seeker and truth sought.

The Platonic path of dialectical ascent, the Aristotelian cultivation of virtue through habituation, the Stoic alignment with cosmic reason, the Buddhist liberation from attachment, the Taoist harmony with natural flow, the Christian surrender to divine love—all these represent methods for the same fundamental transformation: the shift from ego-centered existence to reality-centered being.

This transformation cannot be achieved through reading books or attending lectures, though these may help. It requires the sustained practice of attention, the cultivation of virtue through action, the development of discernment through experience, and the patient endurance of uncertainty while truth gradually reveals itself.

The contemporary crisis of meaning thus represents not a unique historical predicament but the perennial human situation made visible through the stripping away of cultural supports. Every generation must rediscover for itself the eternal truths that make life worth living. Our task is neither to create new values nor to restore old ones, but to awaken to the timeless wisdom that has always been available to those willing to undertake the philosopher’s journey from opinion to knowledge, from appearance to reality, from temporal concerns to eternal truths.

The path remains what it has always been: know thyself, live virtuously, contemplate reality, love wisdom, serve truth. These ancient imperatives shine with renewed urgency in our age of distraction and confusion. They offer not escape from contemporary challenges but the spiritual foundation necessary for meeting them with wisdom, courage, and compassion.

In the end, philosophical and spiritual research represents humanity’s highest calling: the search for meaning that gives meaning to the search itself. This is the Great Work that each soul must undertake, the inner journey that makes all outer journeys worthwhile, the eternal quest that transforms both seeker and sought in the very seeking.

MINI ASSESSMENT: DO YOU HAVE A PHILOSOPHICAL MIND?

The philosophical quest is driven by two fundamental principles: curiosity and the need to know. Philosophers are compelled by an insatiable appetite for knowledge and are conscious of the fact that the pursuit of truth is an ongoing process. What about you?

Read the sentences below and select the ones you agree with and that you think make the most sense.

Count the number of checked boxes and read the corresponding profile.

0: Your mind is anti-philosophical

1-2: Your mind is unphilosophical

3-4: Your mind is prone to philosophy

5-6: You are a true philosopher

MINI TEST: ARE YOU A SPIRITUAL PERSON?

Let’s see if you have an ethereal, transcendental side, or if you are completely absorbed by the material world and its logic. In short, do you know how to take care of your soul as well?

Review the following statements and check the ones you agree with and consider best aligned with your perspective.

Count the number of checked boxes and read the corresponding profile.

0: You are not spiritual at all

1-2: You are hardly spiritual

3-4: You are quite spiritual

5-6: You are very spiritual