Theoretical Foundations and Historical Development

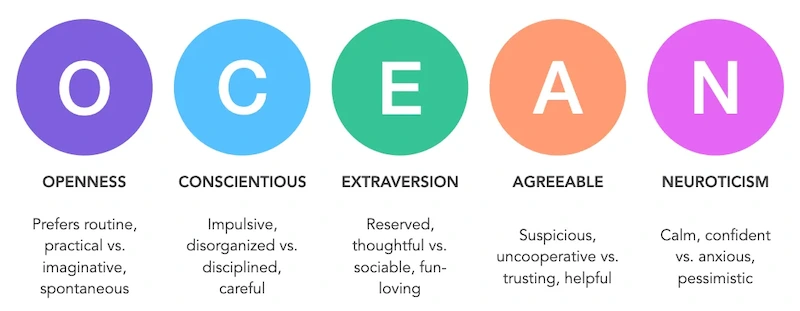

The Big Five Personality Model—commonly known as OCEAN—stands as one of psychology’s most robust frameworks for understanding human personality. This model categorizes the vast spectrum of personality traits into five fundamental dimensions: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Embedded within the tradition of trait theory, this approach posits that individual personality differences manifest as measurable patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior that can be identified through systematic observation and self-assessment.

The intellectual lineage of the Big Five traces back to the pioneering work of mid-20th century psychologists who sought to distill the complexity of human personality into discernible, quantifiable components. Gordon Allport laid crucial groundwork by suggesting that personality could be understood through a constellation of traits—relatively stable patterns of behavior that distinguish individuals from one another. This foundation was subsequently built upon by Raymond Cattell, who employed sophisticated factor analysis techniques to identify underlying patterns in personality descriptors. Cattell’s research initially yielded 16 primary personality factors, though he recognized these could potentially be further refined.

The watershed moment in the development of the Big Five came during the 1980s through the meticulous research of Robert McCrae and Paul Costa. Through exhaustive factor-analytic studies of personality inventories across diverse populations, they synthesized existing findings into what became known as the Five-Factor Model (FFM). Their work conclusively demonstrated that five core dimensions could effectively capture the breadth of human personality variance across cultural boundaries and contextual settings. The model’s elegant simplicity, coupled with its robust empirical support, cemented its position as psychology’s preeminent framework for personality assessment.

Unlike categorical typologies that assign individuals to discrete personality types, the Big Five conceptualizes personality traits along continuous dimensions. This nuanced approach acknowledges that most individuals exist somewhere along a spectrum for each trait rather than at polar extremes, allowing for a more textured and authentic representation of human personality.

The Five Dimensions: A Deeper Examination

1. Openness to Experience

The Explorer’s Mindset

Openness to Experience represents the dimension of cognitive flexibility, intellectual curiosity, and appreciation for novelty, beauty, and unconventional perspectives. This dimension encompasses several interconnected facets:

Imagination and Creativity: Individuals with high openness possess rich, vivid inner worlds. They often engage in creative pursuits that allow them to express their unique perspectives—whether through visual arts, music composition, literary expression, or innovative problem-solving in professional domains. Their thinking tends toward the divergent rather than convergent, generating multiple possibilities rather than focusing on singular solutions.

Intellectual Curiosity: The highly open person exhibits an insatiable appetite for knowledge that extends beyond practical utility. They may pursue learning for its intrinsic pleasure, delving into subjects that capture their interest regardless of immediate application. This curiosity often manifests as a love of reading, engaging with diverse viewpoints, and asking probing questions that challenge established assumptions.

Aesthetic Sensitivity: Those high in openness tend to be deeply moved by artistic expression, natural beauty, and sensory experiences. They may find profound meaning in poetry, music, visual arts, or sublime landscapes—experiences that might affect them emotionally and intellectually at levels beyond mere entertainment or diversion.

Philosophical Inclination: Open individuals often gravitate toward contemplating profound questions about existence, consciousness, ethics, and metaphysics. They may find satisfaction in exploring philosophical systems, religious traditions, or spiritual practices that address the deeper dimensions of human experience.

Cultural Breadth: High openness correlates with appreciation for diverse cultural expressions and traditions. Such individuals often enjoy exploring unfamiliar cuisines, music from different cultural traditions, or literary works from various historical periods and geographical regions.

Conversely, those who score lower on the openness spectrum typically prefer familiar routines and established traditions. They may adopt a more pragmatic, concrete approach to life that values stability over novelty and practical knowledge over theoretical exploration. Such individuals often excel in environments that require consistency, adherence to proven methods, and attention to practical details. Their preference for the familiar should not be misconstrued as intellectual limitation but rather as a different cognitive orientation that values certainty and established structures.

2. Conscientiousness

The Architecture of Achievement

Conscientiousness embodies the capacity for self-discipline, orderliness, and deliberate action toward long-term goals. This dimension encompasses several key aspects:

Industriousness and Work Ethic: Highly conscientious individuals approach tasks with diligence and persistence. They derive satisfaction from productive effort and completing responsibilities to a high standard. Their self-motivation often enables them to remain focused on demanding tasks long after others might abandon them.

Organizational Capacity: Those high in conscientiousness typically maintain orderly physical and mental environments. Their spaces tend to be well-organized, their schedules carefully planned, and their approach to tasks methodical rather than haphazard. This organizational tendency extends to information management, financial planning, and resource allocation.

Reliability and Integrity: Conscientious individuals place high value on fulfilling commitments and maintaining consistency between their words and actions. They tend to be punctual, honor deadlines, and follow through on responsibilities even when doing so requires personal sacrifice or discomfort.

Prudence and Deliberation: Before making significant decisions, highly conscientious people typically engage in thorough consideration of potential consequences and alternatives. They often resist impulsive action in favor of thoughtful planning and evaluation of risks.

Goal-Directed Persistence: Perhaps most characteristically, conscientiousness involves the capacity to delay immediate gratification in service of long-term objectives. This might manifest as saving for retirement instead of indulging immediate desires, maintaining consistent study habits to achieve academic goals, or adhering to health regimens that promise future benefits rather than immediate pleasures.

At the lower end of the conscientiousness spectrum, individuals may exhibit greater spontaneity and flexibility. They might approach life with less rigid planning, allowing for serendipitous discoveries and experiences that might be foreclosed by strict adherence to predetermined schedules. While this approach may sometimes lead to missed deadlines or incomplete tasks, it can also foster creativity and adaptability in rapidly changing circumstances. These individuals may excel in roles that require improvisation, lateral thinking, and comfort with ambiguity.

3. Extraversion

The Social Energy Spectrum

Extraversion encompasses the realm of social engagement, assertiveness, and emotional expressiveness. This dimension manifests through several interconnected facets:

Social Stimulation: Extraverts typically derive energy and vitality from social interaction. They often seek out gatherings, conversations, and collaborative activities that provide opportunities for engagement with others. Unlike introverts, who may feel depleted after extended social contact, extraverts frequently report feeling energized and invigorated following social exchanges.

Assertiveness and Leadership: Those high in extraversion often naturally assume leadership roles in group settings. Their comfort with self-expression enables them to articulate ideas confidently, influence group decisions, and coordinate collective efforts. This assertiveness extends beyond formal leadership to include willingness to advocate for their needs and perspectives in various contexts.

Emotional Expressivity: Extraverts tend toward transparent emotional expression—their feelings are readily apparent through facial expressions, vocal tone, and body language. This expressivity contributes to their often vivacious interpersonal style and can facilitate emotional contagion in group settings.

Sensation-Seeking: Many extraverts demonstrate a pronounced appetite for stimulating experiences. They may gravitate toward adventures, high-energy activities, and novel situations that provide heightened sensory input. This tendency can manifest in preferences for lively environments, physical activities, or experiences that produce excitement.

Conversational Initiative: In social contexts, extraverts typically initiate conversations readily, ask questions, and maintain dialogue flow. Their comfort with verbal expression often enables them to navigate unfamiliar social terrain with relative ease, establishing connections with strangers and expanding their social networks.

At the opposite end of this spectrum, introverts prefer more subdued environments and derive satisfaction from deeper, more intimate social connections rather than broader networks. They often excel at focused, sustained attention and may demonstrate particular strength in reflective thinking, careful observation, and depth of analysis. Contrary to common misconceptions, introversion does not necessarily indicate social anxiety or inability—many introverts possess excellent social skills but simply prefer selective engagement and require solitary time to replenish their energy.

The introversion-extraversion dimension represents different orientations toward stimulation and social energy rather than inherent advantages or deficiencies. In contemporary environments that often privilege extraversion, it’s important to recognize the distinctive contributions that introverted patterns of thought and interaction bring to communities and organizations.

4. Agreeableness

The Compassionate Connection

Agreeableness captures an individual’s orientation toward others on a spectrum from compassionate engagement to competitive self-assertion. This dimension encompasses several interrelated qualities:

Empathic Perspective-Taking: Highly agreeable individuals can intuitively grasp others’ emotional states and cognitive perspectives. This capacity for empathy allows them to respond sensitively to others’ needs and adjust their communication accordingly. Their attunement to emotional nuance often makes them valued confidants and mediators in interpersonal conflicts.

Cooperative Orientation: Those high in agreeableness typically prioritize harmonious relationships over competitive advantage. When conflicts arise, they tend to seek compromise solutions that accommodate multiple stakeholders rather than pursuing maximally advantageous outcomes for themselves. This cooperative tendency extends to willingness to share resources, credit, and opportunities.

Compassionate Concern: Agreeable individuals experience genuine distress when witnessing others’ suffering and derive satisfaction from alleviating such distress. This compassionate concern often manifests in volunteer work, charitable giving, caregiving roles, and consistent small acts of kindness in daily interactions.

Trusting Disposition: High agreeableness correlates with a tendency to assume benevolent intentions in others’ actions. Rather than attributing ambiguous behavior to malice or manipulation, agreeable individuals often give others the benefit of the doubt. While this trusting stance can occasionally lead to exploitation, it generally facilitates smoother social functioning and reduces unnecessary conflict.

Modesty and Humility: Agreeable people typically downplay their own accomplishments and contributions rather than seeking recognition or prestige. They may feel uncomfortable with self-promotion and prefer to highlight others’ contributions to collective achievements.

At the lower end of the agreeableness spectrum, individuals may exhibit greater competitiveness, skepticism, and willingness to challenge others’ perspectives. These traits can be valuable in contexts requiring critical evaluation, negotiation of competing interests, or advancement of unpopular but necessary viewpoints. Less agreeable individuals often excel in roles that require tough decisions that may disappoint or inconvenience others—such as resource allocation, performance evaluation, or enforcement of standards.

The agreeableness dimension does not represent a simple dichotomy between “nice” and “unkind” personalities, but rather different priorities in navigating social relationships—prioritizing either harmony and connection or truth and fairness when these values come into conflict.

5. Neuroticism

The Emotional Sensitivity Dimension

Neuroticism—sometimes reframed as Emotional Stability in its inverse form—represents an individual’s tendency toward experiencing negative emotions and psychological distress. This dimension encompasses several distinct facets:

Anxiety Sensitivity: Those high in neuroticism typically experience heightened vigilance toward potential threats or negative outcomes. This vigilance may manifest as worry about future possibilities, rumination over past events, or heightened awareness of physical sensations that might signal danger. While this sensitivity can sometimes lead to anticipatory problem-solving, it can also generate unnecessary distress when threats fail to materialize.

Emotional Volatility: Neurotic individuals often experience more frequent and intense emotional reactions to life events. Their emotional responses may shift rapidly in response to changing circumstances, and they typically require more time to return to baseline after emotionally activating experiences. This emotional reactivity can provide richness of experience but may also create challenges in maintaining consistent mood states.

Self-Consciousness: High neuroticism correlates with heightened awareness of how one appears to others and concern about potential negative evaluation. This self-consciousness can manifest as social anxiety, performance anxiety, or general discomfort in situations where one might be judged by others.

Vulnerability to Stress: Neurotic individuals typically experience greater physiological and psychological strain under demanding circumstances. Their threshold for experiencing situations as overwhelming tends to be lower than for emotionally stable individuals, potentially leading to earlier exhaustion under sustained pressure.

Negativity Bias: Those high in neuroticism often demonstrate selective attention toward negative information and experiences. They may more readily notice problems, threats, and imperfections while overlooking positive aspects of situations—a perceptual tendency that serves protective functions but can also diminish enjoyment of life experiences.

Individuals low in neuroticism—often described as emotionally stable—typically maintain calm, even dispositions across varying circumstances. They tend to recover quickly from setbacks, approach challenges with confidence, and maintain perspective during stressful periods. Their emotional equilibrium allows them to function effectively under pressure and provides resilience during adversity.

It’s important to recognize that neuroticism, despite its negative connotations in common language, represents a complex trait with potential adaptive functions. The heightened sensitivity associated with neuroticism can enable greater awareness of genuine dangers, motivate preventive behaviors, and foster empathic understanding of others’ distress. Like all personality dimensions, neuroticism exists on a continuum where extreme manifestations may become problematic while moderate levels may serve important psychological functions.

Methodological Framework and Assessment

The Big Five model operates through a sophisticated psychometric framework that translates abstract personality constructs into measurable variables. This transformation occurs through carefully designed assessment instruments that capture behavioral tendencies, emotional patterns, and cognitive preferences through standardized items.

The most common assessment approach involves self-report questionnaires where respondents indicate their agreement or disagreement with statements describing characteristic behaviors or tendencies. These items are typically presented on Likert scales ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” allowing for nuanced positioning along each trait dimension. For example, a conscientiousness assessment might include items like “I follow a schedule” or “I pay attention to details,” while an extraversion measure might include statements such as “I feel comfortable around people” or “I start conversations with strangers.”

Several validated assessment instruments have been developed based on the Big Five framework, varying in length, depth, and specific applications:

NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R): Developed by McCrae and Costa, this comprehensive instrument measures not only the five broad domains but also six specific facets within each domain, providing a highly nuanced personality profile. With 240 items, it offers among the most detailed assessments available.

Big Five Inventory (BFI): A more concise instrument consisting of 44 items that efficiently measures the five core dimensions without detailed facet analysis. This instrument balances brevity with psychometric rigor, making it suitable for research contexts where assessment time is limited.

Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI): An ultra-brief measure designed for situations where personality assessment must be completed quickly. While sacrificing some psychometric precision, this instrument captures broad traits when time constraints make longer assessments impractical.

International Personality Item Pool (IPIP): An open-source collection of personality items that researchers can use to construct customized Big Five assessments for specific research questions or populations.

The psychometric properties of these instruments have been extensively validated through diverse methodologies:

Cross-Cultural Validation: Research across dozens of countries and languages has consistently identified the same five-factor structure, suggesting these dimensions represent universal aspects of human personality rather than culturally specific constructs.

Longitudinal Stability: Studies tracking personality development over decades indicate substantial stability in Big Five traits throughout adulthood, particularly after age 30, though gradual changes do occur across the lifespan.

Observer Agreement: Self-reports of Big Five traits typically show moderate to strong correlations with ratings provided by knowledgeable informants such as spouses, friends, or colleagues, supporting the validity of these constructs beyond subjective self-perception.

Predictive Validity: Big Five dimensions have demonstrated meaningful correlations with significant life outcomes including educational achievement, career success, relationship stability, health behaviors, and longevity—attesting to their practical significance beyond theoretical interest.

The development of computerized adaptive testing has further refined Big Five assessment by tailoring item presentation based on previous responses, potentially increasing measurement precision while reducing the number of items required for accurate assessment.

Limitations and Critiques

Despite its widespread adoption and empirical support, the Big Five model is not without limitations and critiques that warrant consideration when applying this framework:

Self-Report Biases: The predominant assessment methodology relies heavily on individuals’ self-perceptions, which may be distorted by various factors. Social desirability bias may lead respondents to present themselves in culturally valued ways rather than reporting their actual tendencies. Additionally, accurate self-assessment requires substantial self-awareness and introspective capacity that varies considerably among individuals.

Cross-Cultural Applicability: While the five-factor structure generally replicates across cultures, specific behaviors that manifest these traits may vary significantly. What constitutes “conscientious” behavior in one cultural context may differ markedly from another, raising questions about measurement equivalence across cultural boundaries.

Situational Variability: The trait approach presupposes relatively stable behavioral tendencies across situations, yet considerable research demonstrates significant situational influences on behavior. Critics argue that contextual factors often exert stronger effects on specific behaviors than do underlying personality traits, challenging the predictive utility of trait-based models.

Deterministic Implications: Some critics express concern that trait-based approaches may foster deterministic thinking about personality, potentially undermining agency and growth mindsets. Overemphasis on stable traits might discourage efforts toward personal development in areas where individuals believe themselves to be “naturally” limited.

Theoretical Foundations: The Big Five emerged primarily through lexical studies and factor analysis rather than from a unified theoretical framework explaining personality development or functioning. Some theorists argue that while the model effectively describes patterns of behavior, it offers limited explanatory insight into underlying psychological mechanisms.

Granularity Limitations: The five broad domains, while useful for general understanding, may be insufficient for detailed personality assessment needed in clinical contexts or specialized applications. Some researchers advocate for greater attention to specific facets within each dimension rather than focusing exclusively on the broad factors.

Incomplete Coverage: Some personality psychologists argue that important aspects of human personality fall outside the Big Five framework entirely. Potential missing elements include moral character, spirituality, humor styles, emotional intelligence, and culturally specific personality constructs that may not translate readily into the existing five dimensions.

Limited Developmental Perspective: The model primarily describes adult personality patterns rather than developmental trajectories or formative influences. Critics note that understanding how personality develops through childhood and adolescence may require different conceptual frameworks than those applied to adult personality structure.

These limitations highlight the importance of viewing the Big Five as one valuable lens among many for understanding human personality rather than a comprehensive or definitive framework. Integration with other psychological perspectives—including developmental, social cognitive, and neuropsychological approaches—may provide richer understanding than reliance on trait models alone.

Practical Applications Across Domains

The Big Five personality framework has found practical application across numerous domains, demonstrating its versatility and explanatory power:

Psychological Research

The model provides researchers with a standardized taxonomy for investigating personality correlates across diverse domains. This common framework facilitates integration of findings across studies and disciplines, enabling more systematic knowledge accumulation. Specific research applications include:

Behavioral Genetics: Twin and adoption studies using Big Five measures have helped clarify the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors to personality development, with findings suggesting moderate heritability for all five dimensions.

Developmental Psychology: Longitudinal studies track personality stability and change across the lifespan, revealing patterns of developmental trajectories that differ by trait and life stage.

Cultural Psychology: Cross-cultural research examines how personality expression varies across societal contexts while maintaining the same underlying structure, illuminating both universal and culturally specific aspects of human personality.

Health Psychology: Investigations into links between personality traits and health outcomes have identified conscientiousness as a particularly robust predictor of longevity and health-promoting behaviors, while neuroticism often correlates with increased symptom reporting and health anxiety.

Clinical Applications

Mental health professionals utilize Big Five insights to enhance assessment, diagnosis, and treatment planning:

Diagnostic Refinement: Personality profiles can help differentiate between clinical presentations with similar symptoms but different etiologies. For example, distinguishing between depression stemming primarily from high neuroticism versus that emerging from external life circumstances.

Treatment Personalization: Understanding a client’s personality profile enables clinicians to tailor therapeutic approaches to individual characteristics. For instance, highly conscientious clients may respond well to structured cognitive-behavioral protocols, while those high in openness might engage more readily with experiential or existential approaches.

Therapeutic Alliance: Clinician awareness of their own and their clients’ personality traits can facilitate more effective therapeutic relationships by anticipating potential points of connection or friction in the therapeutic process.

Risk Assessment: Certain trait combinations may predispose individuals to specific mental health vulnerabilities. For example, the combination of high neuroticism with low extraversion represents a risk profile for anxiety and depression, potentially enabling preventive interventions for vulnerable individuals.

Organizational Psychology

The corporate world has embraced Big Five assessment for various personnel applications:

Personnel Selection: Organizations use personality assessment to identify candidates whose traits align with job requirements, complementing skills-based evaluation with insight into work styles and team compatibility.

Team Composition: Understanding team members’ personality profiles can inform group composition to ensure productive diversity of perspectives while minimizing potential interpersonal conflicts.

Leadership Development: Executive coaching often incorporates personality assessment to help leaders leverage their natural strengths while developing strategies to compensate for potential blind spots associated with their trait profile.

Career Counseling: Vocational guidance may utilize personality profiles to suggest career paths that align with individuals’ natural tendencies and preferences, potentially enhancing job satisfaction and performance.

Educational Settings

The Big Five framework offers valuable applications in educational contexts:

Learning Style Adaptation: Recognition of personality differences can inform instructional approaches that accommodate diverse student needs. For example, highly introverted students might benefit from opportunities for written reflection, while extraverted learners may thrive with collaborative projects.

Academic Advising: Understanding students’ personality profiles can inform guidance regarding course selection, major declaration, and educational pathways that align with their natural strengths and interests.

Campus Life Programming: Student affairs professionals can design co-curricular programs that appeal to diverse personality types, ensuring that both introverted and extraverted students, traditional and open-minded individuals, find meaningful campus engagement opportunities.

Personal Development

Individual applications of Big Five insights can foster self-understanding and growth:

Self-Awareness: Personality assessment provides a structured framework for understanding one’s characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving—often validating intuitive self-knowledge while also revealing blind spots.

Relationship Insight: Understanding one’s own and significant others’ personality profiles can normalize differences that might otherwise become sources of conflict, fostering appreciation for complementary traits and developing strategies for navigating inherent tensions.

Targeted Development: Recognition of one’s trait profile allows for strategic personal growth efforts that work with rather than against natural tendencies. For example, a highly neurotic individual might focus on developing emotional regulation skills rather than attempting to eliminate sensitivity entirely.

Life Design: Awareness of personality traits can inform major life decisions—from career choice to living arrangements to relationship patterns—in ways that honor authentic preferences rather than conforming to external expectations.

These diverse applications illustrate how the Big Five framework transcends purely academic interest to provide practical value across numerous life domains. By offering a common language for describing individual differences, this model facilitates more nuanced understanding of human behavior in all its complexity and variation.

Conclusion: The OCEAN of Human Personality

The Big Five Personality Model represents one of psychology’s most significant contributions to understanding human individuality. Through its elegant framework of five core dimensions—Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism—it offers a sophisticated yet accessible language for describing the complex tapestry of human personality.

The model’s enduring value stems from its empirical foundations, cross-cultural validity, and predictive utility across diverse life domains. Unlike many psychological theories that remain confined to academic discourse, the Big Five has transcended disciplinary boundaries to inform practices in clinical psychology, organizational development, educational design, and personal growth.

While acknowledging the model’s limitations—including measurement challenges, situational variability, and potential cultural specificity—its continued refinement through research and application speaks to its fundamental soundness. The Big Five does not claim to exhaust the full complexity of human personality, but rather provides a robust starting point for more nuanced exploration of individual differences.

In its essence, the Big Five model reminds us that human personality represents not a collection of discrete types but rather a continuous ocean of possibilities—with each individual occupying a unique position on multiple dimensions of human potential. This perspective honors both our common humanity and our beautiful diversity, inviting deeper understanding of ourselves and greater appreciation for the rich variety of human expression.